Commuting days until retirement: 238

If you have ever spoken at any length to someone who is suffering with a diagnosed mental illness − depression, say, or obsessive compulsive disorder − you may have come to feel that what they are experiencing differs only in degree from your own mental life, rather than being something fundamentally different (assuming, of course, that you are lucky enough not to have been similarly ill yourself). It’s as if mental illness, for the most part, is not something entirely alien to the ‘normal’ life of the mind, but just a distortion of it. Rather than the presence of a new unwelcome intruder, it’s more that the familiar elements of mental functioning have lost their usual proportion to one another. If you spoke to someone who was suffering from paranoid feelings of persecution, you might just feel an echo of them in the back of your own mind: those faint impulses that are immediately squashed by the power of your ability to draw logical common-sense conclusions from what you see about you. Or perhaps you might encounter someone who compulsively and repeatedly checks that they are safe from intrusion; but we all sometimes experience that need to reassure ourselves that a door is locked, when we know perfectly well that it is really.

That uncomfortably close affinity between true mental illness and everyday neurotic tics is nowhere more obvious than with phobias. A phobia serious enough to be clinically significant can make it impossible for the sufferer to cope with everyday situations; while on the other hand nearly every family has a member (usually female, but not always) who can’t go near the bath with a spider in it, as well as a member (usually male, but not always) who nonchalantly picks the creature up and ejects it from the house. (I remember that my own parents went against these sexual stereotypes.) But the phobias I want to focus on here are those two familiar opposites − claustrophobia and agoraphobia.

We are all phobics

In some degree, virtually all of us suffer from them, and perfectly rationally so. Anyone would fear, say, being buried alive, or, at the other extreme, being launched into some limitless space without hand or foothold, or any point of reference. And between the extremes, most of us have some degree of bias one way or the other. Especially so − and this is the central point of my post − in an intellectual sense. I want to suggest that there is such a phenomenon as an intellectual phobia: let’s call it an iphobia. My meaning is not, as the Urban Dictionary would have it, an extreme hatred of Apple products, or a morbid fear of breaking your iPhone. Rather, I want to suggest that there are two species of thinkers: iagorophobes and iclaustrophobes, if you’ll allow me such ugly words.

A typical iagorophobe will in most cases cleave to scientific orthodoxy. Not for her the wide open spaces of uncontrolled, rudderless, speculative thinking. She’s reassured by a rigid theoretical framework, comforted by predictability; any unexplained phenomenon demands to be brought into the fold of existing theory, for any other way, it seems to her, lies madness. But for the iclaustrophobe, on the other hand, it’s intolerable to be caged inside that inflexible framework. Telepathy? Precognition? Significant coincidence? Of course they exist; there is ample anecdotal evidence. If scientific orthodoxy can’t embrace them, then so much the worse for it − the incompatibility merely reflects our ignorance. To this the iagorophobe would retort that we have no logical grounds whatever for such beliefs. If we have nothing but anecdotal evidence, we have no predictability; and phenomena that can’t be predicted can’t therefore be falsified, so any such beliefs fall foul of the Popperian criterion of scientific validity. But why, asks the iclaustrophobe, do we have to be constrained by some arbitrary set of rules? These things are out there − they happen. Deal with it. And so the debate goes.

Archetypal iPhobics

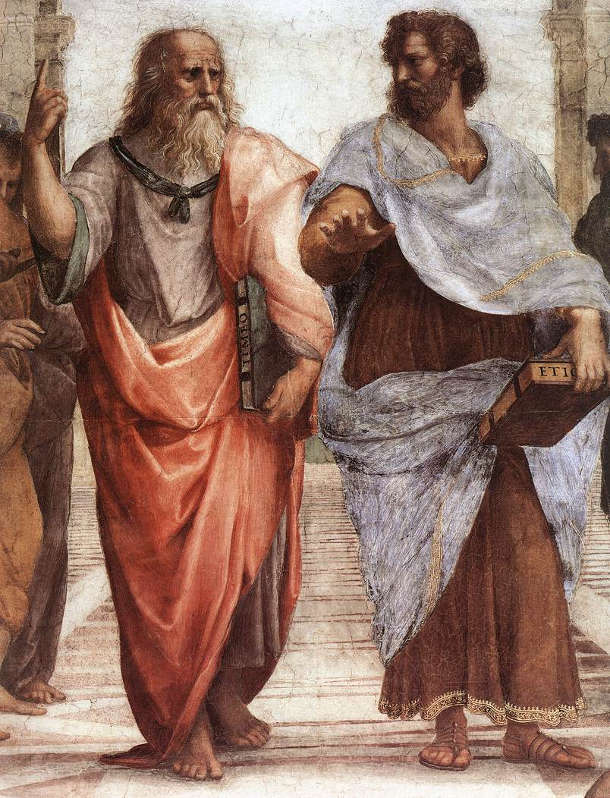

Widening the arena more than somewhat, perhaps the archetypal iclaustrophobe was Plato. For him, the notion that what we see was all we would ever get was anathema – and he eloquently expressed his iclaustrophobic response to it in his parable of the cave. For him true reality was immeasurably greater than the world of our everyday existence. And of course he is often contrasted with his pupil Aristotle, for whom what we can see is, in itself, an inexhaustibly fascinating guide to the nature of our world − no further reality need be posited. And Aristotle, of course, is the progenitor of the syllogism and deductive logic. In Raphael’s famous fresco The School of Athens, the relevant detail of which you see below, Plato, on the left, indicates his world of forms beyond our immediate reality by pointing heavenward, while Aristotle’s gesture emphasises the earth, and the here and now. Raphael has them exchanging disputatious glances, which for me express the hostility that exists between the opposed iphobic world-views to this day.

iPhobia today

It’s not surprising that there is such hostility; I want to suggest that we are talking not of a mere intellectual disagreement, but a situation where each side insists on a reality to which the other has a strong (i)phobic reaction. Let’s look at a specific present-day example, from within the WordPress forums. There’s a blog called Why Evolution is True, which I’d recommend as a good read. It’s written by Jerry Coyne, a distinguished American professor of biology. His title is obviously aimed principally at the flourishing belief in creationism which exists in the US − Coyne has extensively criticised the so-called Intelligent Design theory. (In in my view, that controversy is not a dispute between the two iphobias I have described, but between two forms of iagoraphobia. The creationists, I would contend, are locked up in an intellectual ghetto of their own making, since venturing outside it would fatally threaten their grip on their frenziedly held, narrowly based faith.)

But I want to focus on another issue highlighted in the blog, which in this case is a conflict between the two phobias. A year or so ago Coyne took issue with the fact that the maverick scientist Rupert Sheldrake was given a platform to explain his ideas in the TED forum. Note Coyne’s use of the hate word ‘woo’, often used by the orthodox in science as an insulting reference to the unorthodox. They would defend it, mostly with justification, as characterising what is mystical or wildly speculative, and without evidential basis − but I’d claim there’s more to it than that: it’s also the iagorophobe’s cry of revulsion.

Coyne has strongly attacked Sheldrake on more than one occasion: is there anything that can be said in Sheldrake’s defence? As a scientist he has an impeccable pedigree, having a Cambridge doctorate and fellowship in biology. It seems that he developed his unorthodox ideas early on in his career, central among which is his notion of ‘morphic resonance’, whereby animal and human behaviour, and much else besides, is influenced by previous similar behaviour. It’s an idea that I’ve always found interesting to speculate about − but it’s obviously also a red rag to the iagorophobic bull. We can also mention that he has been careful to describe how his theories can be experimentally confirmed or falsified, thus claiming scientific status for them. He also invokes his ideas to explain aspects of the formation of organisms that, in to date, haven’t been explained by the action of DNA. But increasing knowledge of the significance of what was formerly thought of as ‘junk DNA’ is going a long way to filling these explanatory gaps, so Sheldrake’s position looks particularly weak here. And in his TED talks he not only defends his own ideas, but attacks many of the accepted tenets of current scientific theory.

However, I’d like to return to the debate over whether Sheldrake should be denied his TED platform. Coyne’s comments led to a reconsideration of the matter by the TED editors, who opened a public forum for discussion on the matter. The ultimate, not unreasonable, decision was that the talks were kept available, but separately from the mainstream content. Coyne said he was surprised by the level of invective arising from the discussion; but I’d say this is because we have here a direct confrontation between iclaustrophobes and iagorophobes − not merely a polite debate, but a forum where each side taunts the other with notions for which the opponents have a visceral revulsion. And it has always been so; for me the iphobia concept explains the rampant hostility which always characterises debates of this type − as if the participants are not merely facing opposed ideas, but respective visions which invoke in each a deeply rooted fear.

I should say at this point that I don’t claim any godlike objectivity in this matter; I’m happy to come out of the closet as an iclaustrophobe myself. This doesn’t mean in my case that I take on board any amount of New Age mumbo-jumbo; I try to exercise rational scepticism where it’s called for. But as an example, let’s go back to Sheldrake: he’s written a book about the observation that housebound dogs sometimes appear to show marked excitement at the moment that their distant owner sets off to return home, although there’s no way they could have knowledge of the owner’s actions at that moment. I have no idea whether there’s anything in this − but the fact is that if it were shown to be true nothing would give me greater pleasure. I love mystery and inexplicable facts, and for me they make the world a more intriguing and stimulating place. But of course Coyne isn’t the only commentator who has dismissed the theory out of hand as intolerable woo. I don’t expect this matter to be settled in the foreseeable future, if only because it would be career suicide for any mainstream scientist to investigate it.

Science and iPhobia

Why should such a course of action be so damaging to an investigator? Let’s start by putting the argument that it’s a desirable state of affairs that such research should be eschewed by the mainstream. The success of the scientific enterprise is largely due to the rigorous methodology it has developed; progress has resulted from successive, well-founded steps of theorising and experimental testing. If scientists were to spend their time investigating every wild theory that was proposed their efforts would become undirected and diffuse, and progress would be stalled. I can see the sense in this, and any self-respecting iagorophobe would endorse it. But against this, we can argue that progress in science often results from bold, unexpected ideas that come out of the blue (some examples in a moment). While this more restrictive outlook lends coherence to the scientific agenda, it can, just occasionally, exclude valuable insights. To explain why the restrictive approach holds sway I would look at the how a person’s psychological make-up might influence their career choice. Most iagorophobes are likely to be attracted to the logical, internally consistent framework they would be working with as part of a scientific career; while those of an iclaustrophobic profile might be attracted in an artistic direction. Hence science’s inbuilt resistance to out-of-the-blue ideas.

I may come from the iclaustrophobe camp, but I don’t want to claim that only people of that profile are responsible for great scientific innovations. Take Einstein, who may have had an early fantasy of riding on a light beam, but it was one which led him through rigorous mathematical steps to a vastly coherent and revolutionary conception. His essential iagorophbia is seen in his revulsion from the notion of quantum indeterminacy − his ‘God does not play dice’. Relativity, despite being wholly novel in its time, is often spoken of as a ‘classical’ theory, in the sense that it retains the mathematical precision and predictability of the Newtonian schema which preceded it.

There was a long-standing debate between him and Niels Bohr, the progenitor of the so-called Copenhagen interpretation of quantum theory, which held that different sub-atomic scenarios coexisted in ‘superposition’ until an observation was made and the wave function collapsed. Bohr, it seems to me, with his willingness to entertain wildly counter-intuitive ideas, was a good example of an iclaustrophobe; so it’s hardly surprising that the debate between him and Einstein was so irreconcilable − although it’s to the credit of both that their mutual respect never faltered..

Over to you

Are you an iclaustrophobe or an iagorophobe? A Plato or an Aristotle? A Sheldrake or a Coyne? A Bohr or an Einstein? Or perhaps not particularly either? I’d welcome comments from either side, or neither.