Commuting days until retirement: 408

A long gap since my last post: I can only plead lack of time and brain-space (or should I say mind-space?). Anyhow, here we go with Consciousness 3:

A high point for English Christianity in the 50s: the Queen’s coronation. I can remember watching it on a relative’s TV at the age of 5

I think I must have been a schoolboy, perhaps just a teenager, when I was first aware that the society I had been born into supported two entirely different ways of looking at the world. Either you believed that the physical world around us, sticks, stones, fur, skin, bones – and of course brains – was all that existed; or you accepted one of the many varieties of belief which insisted that there was more to it than that. My mental world was formed within the comfortable surroundings of the good old Church of England, my mother and father being Christians by conviction and by social convention, respectively. The numinous existed in a cosy relationship with the powers-that-were, and parents confidently consigned their children’s dead pets to heaven, without there being quite such a Santa Claus feel to the assertion.

But, I discovered, it wasn’t hard to find the dissenting voices. The ‘melancholy long withdrawing roar’ of the ‘sea of faith’ which Matthew Arnold had complained about in the 19th century was still under way, if you listened out for it. Ever since Darwin, and generations of physicists from Newton onwards, the biological and physical worlds had appeared to get along fine without divine support; and even in my own limited world I was aware of plenty of instances of untimely deaths of innocent sufferers, which threw doubt on God’s reputedly infinite mercy.

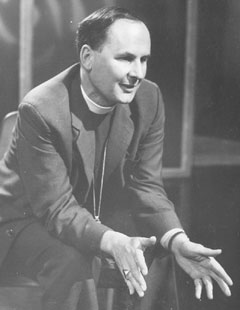

And then in the 1960s a brick was thrown into the calm pool of English Christianity by a certain John Robinson, the Bishop of Woolwich at the time. It was a book called Honest to God, which sparked a vigorous debate that is now largely forgotten. Drawing on the work of other radical theologians, and aware of the strong currents of atheism around him, Robinson argued for a new understanding of religion. He noted that our notion of God had moved on from the traditional old man in the sky to a more diffuse being who was ‘out there’, but considered that this was also unsatisfactory. Any God whom someone felt they had proved to be ‘out there’ “would merely be a further piece of existence, that might conceivably have not been there”. Rather, he says, we must approach from a different angle.

God is, by definition, ultimate reality. And one cannot argue whether ultimate reality exists.

My pencilled zig-zags in the margin of the book indicate that I felt there was something wrong with this at the time. Later, after studying some philosophy, I recognised it as a crude form of Anselm’s ontological argument for the existence of God, which is rather more elegant, but equally unsatisfactory. But, to be fair, this is perhaps missing the point a little. Robinson goes on to say that “one can only ask “what ultimate reality is like – whether it… is to be described in personal or impersonal categories.” His book proceeds to develop the notion of God as in some way identical with reality, rather than as a special part of it. One might cynically characterise this as a response to atheism of the form “if you can’t beat them, join them” – hence the indignation that the book stirred in religious circles.

Teenage reality

But, leaving aside the well worn blogging topic of the existence of God, there was the teenage me, still wondering about ‘ultimate reality’, and what on earth, for want of a better expression, that might be. Maybe the ‘personal’ nature of reality which Robinson espoused was a clue. I was a person, and being a person meant having thoughts, experiences – a self, or a subjective identity. My experiences seemed to be something quite other from the objective world described by science – which, according to the ‘materialists’ of the time, was all that there was. What I was thinking of then was the topic of my previous post, Consciousness 2 – my qualia, although I didn’t know that word at the time. So yes, there were the things around us (including our own bodies and brains), our knowledge and understanding of which had been, and was, advancing at a great rate. But it seemed to me that no amount of knowledge of the mechanics of the world could ever explain these private, subjective experiences of mine (and I assumed, of others). I was always strongly motivated to believe that there was no limit to possible knowledge – however much we knew, there would always be more to understand. Materialsm, on the other hand, seemed to embody the idea of a theoretically finite limit to what could be known – a notion which gave me a sense of claustrophobia (of which more in a future post).

So I made my way about the world, thinking of my qualia as the armour to fend off the materialist assertion that physics was the whole story. I had something that was beyond their reach: I was a something of a young Cartesian, before I had learned about Descartes. It was a another few years before ‘consciousness’ became a legitimate topic of debate in philosophy and science. One commentator I have read dates this change to the appearance of Nagel’s paper What is it like to be a Bat in 1973, which I referred to in Consciousness 1. Seeing the debate emerging, I was tempted to preen myself with the horribly arrogant thought that the rest of the world had caught up with me.

The default position

Philosophers and scientists are still seeking to find ways of assimilating consciousness to physics: such physicalism, although coming in a variety of forms, is often spoken of as the default, orthodox position. But although my perspective has changed quite a lot over the years, my fundamental opposition to physicalism has not. I am still at heart the same naive dualist I was then. But I am not a dogmatic dualist – my instinct is to believe that some form of monism might ultimately be true, but beyond our present understanding. This consigns me into another much-derided category of philosophers – the so-called ‘mysterians’.

But I’d retaliate by pointing out that there is also a bit of a vacuum at the heart of the physicalist project. Thoughts and feelings, say its supporters, are just physical things or events, and we know what we mean by that, don’t we? But do we? We have always had the instinctive sense of what good old, solid matter is – but you don’t have to know any physics to realise there are problems with the notion. If something were truly solid it would entail that it was infinitely dense – so the notion of atomism, starting with the ancient Greeks, steadily took hold. But even then, atoms can’t be little solid balls, as they were once imagined – otherwise we are back with the same problem. In the 20th century, atomic physics confirmed this, and quantum theory came up with a whole zoo of particles whose behaviour entirely conflicted with our intuitive ideas gained from experience; and this is as you might expect, since we are dealing with phenomena which we could not, in principle, perceive as we perceive the things around us. So the question “What are these particles really like?” has no evident meaning. And, approaching the problem from another standpoint, where psychology joins hands with physics, it has become obvious that the world with which we are perceptually familiar is an elaborate fabrication constructed by our brains. To be sure, it appears to map on to the ‘real’ world in all sorts of ways, but has qualities (qualia?) which we supply ourselves.

Truth

So what true, demonstrable statements can be made about the nature of matter? We are left with the potently true findings – true in the the sense of explanatory and predictive power – of quantum physics. And, when you’ve peeled away all the imaginative analogies and metaphors, these can only be expressed mathematically. At this point, rather unexpectedly, I find myself handing the debate back to our friend John Robinson. In a 1963 article in The Observer newspaper, heralding the publication of Honest to God, he wrote:

Professor Herman Bondi, commenting in the BBC television programme, “The Cosmologists” on Sir James Jeans’s assertion that “God is a great mathematician”, stated quite correctly that what he should have said is “Mathematics is God”. Reality, in other words, can finally be reduced to mathematical formulae.

In case this makes Robinson sound even more heretical than he in fact was, I should note that he goes on to say that Christianity adds to this “the deeper reliability of an utterly personal love”. But I was rather gratified to find this referral to the concluding thoughts of my post by the writer I quoted at the beginning.

I’m not going to speculate any further into such unknown regions, or into religious belief, which isn’t my central topic. But I’d just like to finish with the hope that I have suggested that the ‘default position’ in current thinking about the mind is anything but natural or inevitable.