Commuting days until retirement: 300

Imagine a book. It’s a thick, heavy, distinguished looking book, with an impressive tooled leather binding, gilt-trimmed, and it has marbled page edges. A glance at the spine shows it to be a copy of Shakespeare’s complete works. It must be like many such books to be found on the shelves of libraries or well-to-do homes around the world at the present time, although it is not well preserved. The binding is starting to crumble, and much of the gilt lettering can no longer be made out. There’s also something particularly unexpected about this book, which accounts for the deterioration. Let your mental picture zoom out, and you see, not a set of book-laden shelves, or a polished wood table bearing other books and papers, but an expanse of greyish dust, bathed in bright, harsh light. The lower cover is half buried in this dust, to a depth of an inch or so, and some is strewn across the front, as if ithe book had been dropped or thrown down. Zoom out some more, and you see a rocky expanse of ground, stretching away to what seems like a rather close, sharply defined horizon, separating this desolate landscape from a dark sky.

Yes, this book is on the moon, and it has been the focus of a long standing debate between my brother and sister-in-law. I had vaguely remembered one of them mentioning this some years back, and thought it would be a way in to this piece on intentionality, a topic I have been circling around warily in previous posts. To clarify: books are about things – in fact our moon-bound book is about most of the perennial concerns of human beings. What is it that gives books this quality of ‘aboutness’ – or intentionality? When all’s said and done our book boils down to a set of inert ink marks on paper. Placing it on the moon, spatially distant, and and perhaps temporally distant, from human activity, leaves us with the puzzle as to how those ink marks reach out across time and space to hook themselves into that human world. And if it had been a book ‘about’, say, physics or astronomy, that reach would have been, at least in one sense, wider.

Which problem?

Well, I thought that was what my brother and sister-in-law had been debating when I first heard about it; but when I asked them it turned out that their what they’d been arguing about was the question of literary merit, or more generally, intrinsic value. The book contains material that has been held in high regard by most of humanity (except perhaps GCSE students) for hundreds of years. At some distant point in space and time, perhaps after humanity has disappeared, does that value survive, contained within it, or is it entirely dependent upon who perceives and interprets it?

Two questions, then – let’s refer to them as the ‘aboutness’ question and the ‘value’ question. Although the value question wasn’t originally within the intended scope of this post, it might be worth trying to tease out how far each question might shed light on the other.

What is a book?

First, an important consideration which I think has a bearing on both questions – and which may have occurred to you already. The term ‘book’ has at least two meanings. “Give me those books” – the speaker refers to physical objects, of the kind I began the post with. “He’s written two books” – there may of course be millions of copies of each, but these two books are abstract entities which may or may not have been published. Some years back I worked for a small media company whose director was wildly enthusiastic about the possibilities of IT (that was my function), but somehow he could never get his head around the concepts involved. When we discussed some notional project, he would ask, with an air of addressing the crucial point, “So will it be a floppy disk, or a CD-ROM?” (I said it was a long time ago.) In vain I tried to get it across to him that the physical instantiation, or the storage medium, was a very secondary matter. But he had a need to imagine himself clutching some physical object, or the idea would not fly in his mind. (I should have tried to explain by using the book example, but never thought of it at the time.)

So with this in mind, we can see that the moon-bound Shakespeare is what is sometimes called in philosophy an ‘intuition pump’ – an example intended to get us thinking in a certain way, but perhaps misleadingly so. This has particular importance for the value question, it seems to me: what we value is set of ideas and modes of expression, not some object. And so its physical, or temporal, location is not really relevant. We could object that there are cases where this doesn’t apply – what about works of art? An original Rembrandt canvas is a revered object; but if it were to be lost it would live on in its reproductions, and, crucially, in people’s minds. Its loss would be sharply regretted – but so, to an extent, would the loss of a first folio edition of Shakespeare. The difference is that for the Rembrandt, direct viewing is the essence of its appreciation, while we lose nothing from Shakespeare when watching, listening or reading, if we are not in the presence of some original artefact.

Value, we might say, does not simply travel around embedded in physical objects, but depends upon the existence of appreciating minds. This gives us a route into examination of the value question – but I’m going to put that aside for the moment and return to good old ‘aboutness’ – since these thoughts also give us some leverage for developing our ideas there.

…and what is meaning?

So are we to conclude that our copy of Shakespeare itself, as it lies on the moon, has no intrinsic connection with anything of concern or meaning to us? Imagine that some disaster eliminated human life from the earth. Would the book’s links to the world beyond be destroyed at the same time, the print on its pages suddenly reduced to meaningless squiggles? This is perhaps another way in which we are misled by the imaginary book.

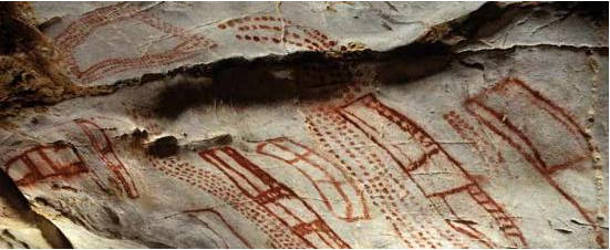

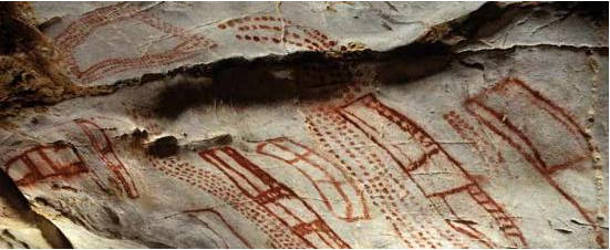

A 40,000 year old cave painting in the El Castillo Cave in Puente Viesgo, Spain (www.spain.info)

Think of prehistoric cave paintings which have persisted, unseen, thousands of years after the deaths of those for whom they were particularly meaningful. Eventually they are found by modern men who rediscover some meaning in them. Many of them depict recognisable animals – perhaps a food source for the people of the time; and as representational images their central meaning is clear to us. But of course we can only make educated guesses at the cloud of associations they would have had for their creators, and their full significance in their culture. And other ancient cave wall markings have been discovered which are still harder to interpret – strange abstract patterns of dots and lines (see above). What’s interesting is that we can sense that there seems to have been some sort of purpose in their creation, without having any idea what it might have been.

A detail from the Luttrell Psalter (Bristish Library)

Let’s look at a more recent example: the marvellous illuminated script of the Luttrell Psalter, the 14th century illuminated manuscript, now in the British Library. (you can view it in wonderful detail by going to the British Library’s Turning the Pages application.) It’s a psalter, written in Latin, and so the subject matter is still accessible to us. Of more interest are the illustrations around the text – images showing a whole range of activities we can recognise, but as they were carried on in the medieval world. This of course is a wonderful primary historical source, but it’s also more than that. Alongside the depiction of these activities is a wealth of decoration, ranging from simple flourishes to all sorts of fantastical creatures and human-animal hybrids. Some may be symbols which no longer have meaning in today’s culture, and others perhaps just jeux d’esprit on the part of the artist. It’s mostly impossible now for us to distinguish between these.

Think also of the ‘authenticity’ debate in early music that I mentioned in Words and Music a couple of posts back. The full, authentic effect of a piece of music composed some hundreds of years ago, so one argument goes, could only affect an audience as the composer intended if the audience were also of his time. Indeed, even today’s music, of any genre, will have different associations for, and effects on, a listener depending on their background and experience. And indeed, it’s quite common now for artists, conceptual or otherwise, to eschew any overriding purpose as to the meaning of their work, but to intend each person to interpret it in his or her own idiosyncratic way.

Rather too many examples, perhaps, to illustrate the somewhat obvious point that meaning is not an intrinsic property of inert symbols, such as the printed words in our lunar Shakespeare. In transmitting their sense and associations from writer to reader the symbols depend upon shared knowledge, cultural assumptions and habits of thought; something about the symbols, or images, must be recognisable by both creator and consumer. When this is not the case we are just left with a curious feeling, as when looking at that abstract cave art. We get a a strong sense of meaning and intention, but the content of the thoughts behind it are entirely unknown to us. Perhaps some unthinkably different aliens will have the same feeling on finding the Voyager robot spacecraft, which was sent on its way with some basic information about the human race and our location in the galaxy. Looking at the cave patterns we can detect that information is present – but meaning is more than just information. Symbols comprise the latter without intrinsically containing the former, otherwise we’d be able to know what those cave patterns signified.

Physical signs can’t embody meaning of themselves, apart from the creator and the consumer, any more than a saw can cut wood without a carpenter to wield it. Tool use, indeed, in early man or advanced animals, is an indicator of intentionality – the ability to form abstract ‘what if’ concepts about what might be done, before going ahead and doing it. A certain cinematic moment comes to mind: in Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, where the bone wielded as a tool by the primate creature in the distant past is thrown into the air, and cross-fades into a space ship in the 21st century.

Here be dragons

Information theory developed during the 20th century, and is behind all the advances of the period in computing and communications. Computers are like the examples of symbols we have looked at: the states of their circuits and storage media contain symbolic information but are innocent of meaning. Which thought, it seems to me, it leads us to the heart of the perplexity around the notion of aboutness, or intentionality. Brains are commonly thought of as sophisticated computers of a sort, which to some extent at least they must be. So how come that when, in a similar sort of way, information is encoded in the neurochemical states of our brains, it is magically invested with meaning? In his well-known book A Brief History of Time, Stephen Hawking uses a compelling phrase when reflecting on the possibility of a universal theory. Such a theory would be “just a set of rules and equations”. But, he asks,

What is it that breathes fire into the equations and makes a universe for them to describe?

I think that, in a similar spirit, we have to ask: what breathes fire into our brain circuits to add meaning to their information content?

The Chinese Room

If you’re interested enough to have come this far with me, you will probably know about a famous philosophical thought experiment which serves to support the belief that my question is indeed a meaningful and legitimate one – John Searle’s ‘Chinese Room’ argument. But I’ll explain it briefly anyway; skip the next paragraph if you don’t need the explanation.

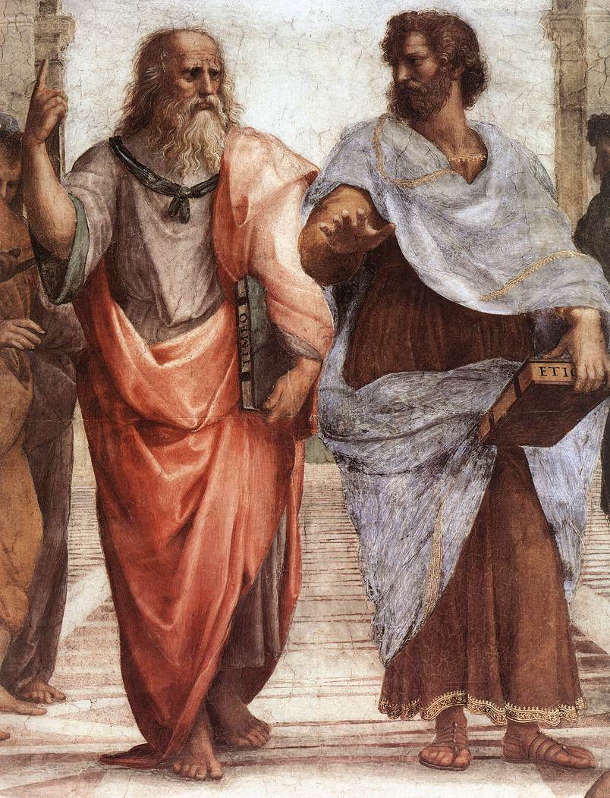

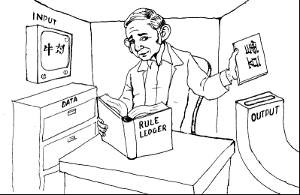

A visualisation of John Searle inside the Chinese Room

Searle imagines himself cooped up in a rather bizarre room where he can only communicate with the outside world by passing and receiving notes through an aperture. Within the room he is equipped only with an enormous card filing system containing a set of Chinese characters and rules for manipulating them. He has Chinese interlocutors outside the room, who pass in pieces of paper bearing messages in Chinese. Unable to understand Chinese, he goes through a cumbersome process of matching and manipulating the Chinese symbols using his filing system. Eventually this process yields a series of characters as an answer, which are transcribed on to another piece of paper and passed back out. The people outside (if they are patient enough) get the impression that they are having a conversation with someone inside the room who understands and responds to their messages. But, as Searle says, no understanding is taking place inside the room. As he puts it, it deals with syntax, not semantics, or in the terms we have been using, symbols, not meaning. Searle’s purpose is to demolish the claims of what he calls ‘strong AI’ – the claim that a computer system with this sort of capability could truly understand what we tell it, as judged from its ability to respond and converse. The Chinese Room could be functionally identical to such a system (only much slower) but Searle is demonstrating that is is devoid of anything that we could call understanding.

If you have an iPhone you’ll probably have used an app called ‘Siri’ which has just this sort of capability – and there are equivalents on other types of phone. When combined with the remote server that it communicates with, it can come up with useful and intelligent answers to questions. In fact, you don’t have to try very hard to make it come up with bizarre or useless answers, or flatly fail. But that’s just a question of degree – no doubt future versions will be more sophisticated. We might loosely say that Siri ‘understands’ us – but of course it’s really just a rather more efficient Chinese Room. Needless to say, Searle’s argument has generated years of controversy. I’m not going to enter into that debate, but will just say that I find the argument convincing; I don’t think that Siri can ‘understand’ me.

So if we think of understanding as the ‘fire’ that’s breathed into our brain circuits, where does it come from? Think of the experience of reading a gripping novel. You may be physically reading the words, but you’re not aware of it. ‘Understanding’ is hardly an issue, in that it goes without saying. More than understanding, you are living the events of the novel, with a succession of vivid mental images. Another scenario: you are a parent, and your child comes home from school to tell you breathlessly about some playground encounter that day – maybe positive or negative. You are immediately captivated, visualising the scene, maybe informed by memories of you own school experiences. In both of these cases, what you are doing is not really to do with processing information – that’s just the stimulus that starts it all off. You are experiencing – the information you recognise has kicked off conscious experiences; and yes, we are back with our old friend consciousness.

Understanding and consciousness

Searle also links understanding to consciousness; his position, as I understand it, is that consciousness is a specifically biological function, not to be found in clever artefacts such as computers. But he insists that it’s purely a function of physical processes nontheless – and I find it difficult to understand this view. If biologically evolved creatures can produce consciousness as a by-product of their physical functioning, how can he be so sure that computers cannot? He could be right, but it seems to be a mere dogmatic assertion. I agree with him that you can’t have meaning – and hence intentionality – without consciousness. For sure, although he denies it, he leaves open the possibility that a computer (and thus, presumably, the Chinese Room as a whole) could be conscious. But he does have going for him the immense implausibility of that idea.

How much intentionality?

So does consciousness automatically bring intentionality with it? In my last post I referred to a dog’s inability to understand or recognise a pointing gesture. We assume that dogs have consciousness of some sort – in a simpler form, they have some of the characteristics which lead us to assume that other humans like ourselves have it. But try thinking yourself for a moment into what it might be to inhabit the mind of a dog. Your experiences consist of the here and now (as ours do) but probably not a lot more. There’s no evidence that a dog’s awareness of the past consists of more than simple learned associations of a Pavlovian kind. They can recognise ‘walkies’, but it seems a mere trigger for a state of excitement, rather than a gateway to a rich store of memories. And they don’t have the brain power to anticipate the future. I know some dog owners might dispute these points – but even if a dog’s awareness extends beyond ‘is’ to ‘was’ and ‘will be’, it surely doesn’t include ‘might be’ or ‘could have been’. Add to this the dog’s inability to use offered information to infer that the mind of another individual contains a truth about the world that hitherto has not been in your own mind (i.e. the ability to understand pointing – see the previous post) and it starts to become clearer what is involved in intentionality. Mere unreflective experiencing of the present moment doesn’t lead to the notion of the objects of your thought, as disticnct from the thought itself. I don’t want to offend dog-owners – maybe their pets’ abilites extend beyond that; but there are certainly other creatures – conscious ones, we assume – who have no such capacity.

So intentionality requires consciousness, but isn’t synonymous with it: in the jargon, consciousness is necessary but not sufficient for intentionality. As hinted earlier, the use of tools is perhaps the simplest indicator of what is sufficient – the ability to imagine how something could be done, and then to take action to make it a reality. And the earliest surviving evidence from prehistory of something resembling a culture is taken to be the remains of ancient graves, where objects surrounding a body indicate that thought was given to the body’s destiny – in other words, there was a concept of what may or may not happen in the future. It’s with these capabilities, we assume, that consciousness started to co-exist with the mental capacity which made intentionality possible.

So some future civilisation, alien or otherwise, finding that Shakespeare volume on the moon, will have similar thoughts to those that we would have on discovering the painted patterns in the cave. They’ll conclude that there were beings in our era who possessed the capacity for intentionality, but they won’t have the shared experience which enables them to deduce what the printed symbols are about. And, unless they have come to understand better than we do what the nature of consciousness is, they won’t have any better idea what the ultimate nature of intentionality is.

The value of what they would find is another question, which I said I would return to – and will. But this post is already long enough, and it’s too long since I last published one – so I’ll deal with that topic next time.

I’m not sure exactly what originally put me on to the first one of this pair; but I do remember reading someone’s opinion that this was the ‘perfect novel’. Looking around, there are encomiums everywhere. Carmen Callil, the Virago publisher, republished the book in 1983 (it originally appeared in 1954), calling it ‘one of my favourite classics’. Jilly Cooper considers it ‘my best book of almost all time’. The author, Elizabeth Jenkins, died only recently, in 2010, at the age of 104. Her Guardian obituary mentions the book as ‘one of the outstanding novels of the postwar period’. The publisher has given it an introduction by none other than Hilary Mantel – a writer whose abilities I respect, having read and enjoyed the first two books in her Thomas Cromwell trilogy. She writes: ‘I have admired this exquisitely written novel for many years…’

I’m not sure exactly what originally put me on to the first one of this pair; but I do remember reading someone’s opinion that this was the ‘perfect novel’. Looking around, there are encomiums everywhere. Carmen Callil, the Virago publisher, republished the book in 1983 (it originally appeared in 1954), calling it ‘one of my favourite classics’. Jilly Cooper considers it ‘my best book of almost all time’. The author, Elizabeth Jenkins, died only recently, in 2010, at the age of 104. Her Guardian obituary mentions the book as ‘one of the outstanding novels of the postwar period’. The publisher has given it an introduction by none other than Hilary Mantel – a writer whose abilities I respect, having read and enjoyed the first two books in her Thomas Cromwell trilogy. She writes: ‘I have admired this exquisitely written novel for many years…’ Straight away we find a cast of characters which have all the idiosyncrasies, mixed motives and secrets that you’d expect in authentic, three-dimensional people. There’s the odd household consisting of two sisters – one damaged in a car accident, and one widowed, who fretfully runs the household, which includes a guest-house – and her daughter who has learning difficulties, as they wouldn’t have been called then. Alongside them is another widow, whose MP husband has recently drowned in a boating accident which their traumatised son survived, and the friend with whom she distracts herself in various random enthusiasms, including covert betting on horses. Into this circle is introduced Vinny, the slightly mysterious single man (some of whose mysteries are revealed later) and his insufferable headstrong mother. (“At least you know where you are with her, ” comments one character. “But you don’t want to be there, ” retorts another.)

Straight away we find a cast of characters which have all the idiosyncrasies, mixed motives and secrets that you’d expect in authentic, three-dimensional people. There’s the odd household consisting of two sisters – one damaged in a car accident, and one widowed, who fretfully runs the household, which includes a guest-house – and her daughter who has learning difficulties, as they wouldn’t have been called then. Alongside them is another widow, whose MP husband has recently drowned in a boating accident which their traumatised son survived, and the friend with whom she distracts herself in various random enthusiasms, including covert betting on horses. Into this circle is introduced Vinny, the slightly mysterious single man (some of whose mysteries are revealed later) and his insufferable headstrong mother. (“At least you know where you are with her, ” comments one character. “But you don’t want to be there, ” retorts another.)